In connection with the Lagodekhi survey project – in particular with the attempt to establish a complete list of the kurgans (barrow graves) of the municipality, which has been the main aim of Stefania Fiori’s MA degree at Ca’ Foscari University (2020) – and with the expedition’s interest for the 3rd millennium Bedeni culture as a possible future topic of research, some geo-archaeological work and non invasive prospections were carried out on site LS034 (= Ananauri kurgan 9, UTM 38 T 580785 E 4623749 N, alt. 236 a.s.l.). This is a ca 70 m large kurgan belonging to the large cluster of monumental Bedeni barrows located in the forest to the south of the present Ananauri/Onanauri village. Three of these have been excavated in recent years, yielding quite sensational results: Ananauri kurgans 1 and 2 (W. Orthmann, Burial Mounds of the Martqopi and Bedeni Cultures in Eastern Georgia, in E. Rova, M. Tonussi (eds.), At the Northern Frontier of Near Eastern Archaeology: Recent Research on Caucasia and Anatolia in the Bronze Age, Turnhout 2017, 189-199) and Ananauri Kurgan 3 (Z. Makharadze et al., Ananauri Big Kurgan n. 3, Tbilisi 2016).

There remained, however, some open questions concerning these monumental structures, on which we decided to concentrate our research. The first one concerns the original environmental conditions of the Alazani valley when the kurgans were built and, in particular, the level of the plain at that time (second half of the 3rd millennium BC) and the successive rate of deposits accumulation until the present day, to be compared with the results of soundings carried out in 2018 and 2019 the Tsiteli Gorebi region for a better understanding of the evolution of the Lagodekhi municipality territory in the course of the last millennia. To clarify this issue, Giovanni Boschian dug a 4 x 1 m sounding just outside of the kurgan perimeter (Fig. 12). The following is a summary of his results.

The exposed sequence of lithologic units, from top downwards, includes:

0. Forest soil. Several rounded cobbles lie on the surface at the southernmost edge of the trench. Thickness 10-12 cm, abrupt limit.

1. Light brownish silty loam. Common rounded cobbles occur sparsely throughout the layer. Thickness about 20 cm, clear limit. No cultural remains.

2. Yellowish brown silty loam, homogeneous and rather compact. Sparse coarse cobbles. Thickness 70-80 cm, sharp limit. No cultural remains.

3.1. Unit composed of large cobbles, often > 25 cm, lying at the bottom of unit 2. To the southern side of the trench these cobbles can be superimposed in 2-3 layers, whereas their density and thickness deceases northwards. Thickness 0 to 30-40 cm, sharp limit. No cultural remains.

4. Greyish-brownish silty clay loam, very compact. Thickness not observed. No cultural remains.

Unit 4 represents a medium developed soil, developed on alluvial sediments that can be dated to some still undetermined period before the building of the kurgan. It also indicates that river sediment deposition stopped or was negligible, so that a soil could develop on the surface of the sediments. The topsoil was partially removed when the kurgan was built. Due to the small area of the trench, it is difficult to determine whether the cobbles of unit 3.1 represent the decay of a wall encircling the kurgan, or simply the colluvium of a layer of cobbles set onto its surface. In any case, this process started rather early after the construction of the kurgan, as no river sediments similar to those of the overlying unit 2 occur under unit 3.1. More correctly, it may be simply hypothesised that the decay of the structure had already started before the following alluvial phase testified by unit 2. Age and duration of this phase are still undetermined, as no cultural remains were found within the sequence. It can be concluded that the average deposition rate from the mid-third millennium (foundation of the kurgan) to now is about 80 cm of river sediments. However, it must be pointed out that alluvial deposition rates can be highly variable in time, and that erosion processes may alter the real thickness of the deposits, indicating rates that are apparently lower than the real ones.

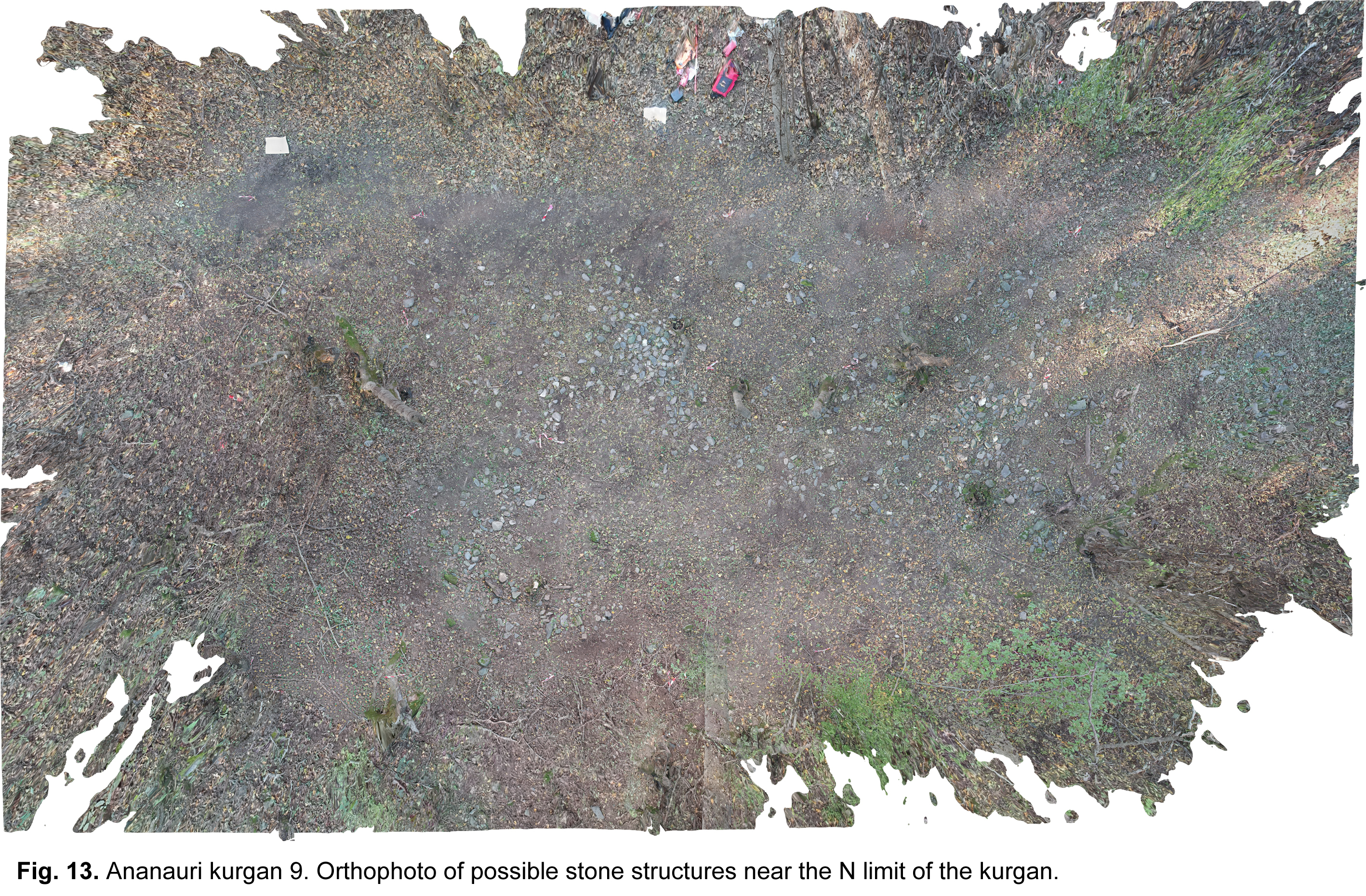

The second research question concerns the possible presence of anthropic features around the kurgans. The whole setting of the kurgans, including possible accessory features around the main building, is poorly documented in Georgia. However, some information about encircling walls, paved roads and other features is documented in literature (G. Narimanishvili, Ritual Roads at Trialeti Barrows, Journal of .Georgian Archaeology 1, 2004, 120-124). To tackle this question, we first of all observed with special care the area surrounding the kurgan, where we noticed that the amount of pebblestones lying at its foot was not more or less homogeneous, as it should be if it were simply the result of slopewash, but there were some areas of more dense accumulation. We thus decided to concentrate on one of these, located on the northern side of the kurgan. By cleaning the soil from fallen leaves and wood, we observed the presence of some possible alignments of stones running roughly perpendicular to each other (as visible in the drone orthophoto (Fig. 13), the presence and meaning of which must await future investigations.

We also decided to undertake some preliminary Ground-Penetrating Radar investigations on the kurgan and its surroundings, in order to clarify its internal structure and the possible existence of buried structures around it. These were carried out by Guram Sharashenidze (Tbilisi). First of all, two roughly perpendicular profiles were performed along the EW and respectively NS sections of the kurgan. The first was 130 m long and included the whole kurgan and the area surrounding it; the second was ca 80 m long (i.e. it missed the E slope of the mound and the neighbouring plain area). Secondly, two areas of 12 x 10 and 7 x 10 m on the plain area joining the bottom of the kurgan on its northern and western sides, close to the spot where the cluster of cobblestones had been identified, were covered by perpendicular profiles at a distance of ca 2 m from each other.

The investigations were performed on the very last days of the season, and the elaboration of their results is still under way. One preliminary result is the possible presence, around the circumference of mound at a distance of ca 5 m from this, of an annular buried structure of stones, of which no trace is visible on the surface.

Some work was also carried out at site LS075 (UTM 38T 4616702 E 586924 N, alt. 210 a.s.l.), which during the 2019 survey season had been identified as a possible settlement site in the Alazani lowland forest area. Here, two 1 x 2 m wide geological soundings were excavated on the top of the hill at a distance of 50 m from each other. The first one (Test Trench 1) reached a depth of 170 cm, while the second one (Test Trench 2) was stopped at a depth of ca 65 cm from the top, after meeting an apparently similar sequence. In Test Trench 1, under a ca 35cm-thick layer of dark humus (locus 001), where we found some sparse archaeological material (a number of pottery sherds, mainly of Hellenistic date, some obsidian fragments, some animal bones) we met a 50cm-thick layer of yellowish lime with abundant calcium carbonate particles (loci 002-003), underlain by a series of sub-horizontal layers of fine sediments of different colours (loci 0004a, b, c, total depth 65 cm) and, finally, by a very hard layer of whitish yellowish sediments which was not completely excavated. All of these layer were completely devoid on any artefacts or other traces of human activities. We thus concluded that the site was the seat of a short-lived occupation during the Hellenistic period, and, possibly, of sporadic human frequentation during the Chalcolithic and the Bronze Age, but that the rest of its stratigraphical sequence was of natural origin. It remains to be explained, however, how a similar mounded site could develop in the middle of the flat Alazani plain.